Last week (Mar. 16), Somali pirates finally released a Comoros-flagged oil tanker that they seized off the coast of Somalia a few days earlier. They agreed to forego their demand for ransom after learning that a Somali businessman had hired the ship to take oil from Djibouti to the Somali capital, Mogadishu.

Last week (Mar. 16), Somali pirates finally released a Comoros-flagged oil tanker that they seized off the coast of Somalia a few days earlier. They agreed to forego their demand for ransom after learning that a Somali businessman had hired the ship to take oil from Djibouti to the Somali capital, Mogadishu.

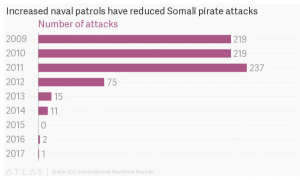

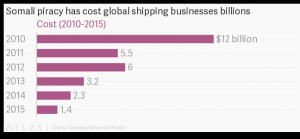

The incident was evidence for those who argue piracy off the Somali shores isn’t over yet despite it being the first major pirate attack since 2012. For such people, it also showed some of the motives that led to its piracy’s original emergence still persist. Ship hijacks and attacks in Somali waters were a very regular occurrence between 2009 to 2011 but have been out of the news for several years. Yet they were seared into global public consciousness in 2013 by the Tom Hanks’ Hollywood movie, Captain Phillips, which dramatized a traumatic ship hijack by Somali pirates.

Even with the overall decline of the anti-piracy industry, “the Somali coast was and still is a high-risk area,” says Ousa Okello, an international maritime lawyer based in Mombasa. Vessels have continued to report suspicious activity related to piracy and attempted attacks.

Protection vs. piracy

The attack on the Aris 13 oil tanker was the first successful hijack for ransom since 2012. The pirates who attacked it said they were frustrated fishermen out to defend their waters from foreign vessels that destroy their equipment during expeditions.

Originally, piracy acted as a deterrent and chased some illegal trawlers, says Timothy Walker, a maritime security researcher at the Institute for Security Studies. But the counter-piracy patrols, whose mandate does not extend to preventing illegal fishing, has created a situation where “many perceive the patrols as protecting their own fishing fleets.” This “creates an atmosphere of mistrust and suspicion in which old grievances and current concerns interact.”

In Nov. 2016, after a sharp decrease in attacks, NATO ended its anti-piracy mission in Somalia. The international coordinated effort has been successful in protecting ships and providing them with best industry practices.

Weak fishing industry

Somalia has the longest coastline in continental Africa—over 3,300 kilometers of turquoise beaches and ports. But the country’s fishing industry is small-scale and lacks the requisite institutional structure to support it.

A UN report estimated that $300 million worth of seafood is stolen from Somalia’s coastline every year. But with the right policies and production, the fisheries sector could provide food security, employment, and contribute to the growth of the economy.

Piracy must also be seen as part of a broader problem that requires common African solutions. Somalia’s new central government should engage its own regional states, clans and business community to forestall piracy.

Neighboring countries should also “look to Somalia’s coast as a potential for further growth,” says Okello.

Source: Quartz